Finding a more intuitive approach to determining the acceleration of two objects attached to a pulley

The title is a bit of a mouthful, but I'll explain what we're trying to do here. Consider the following:

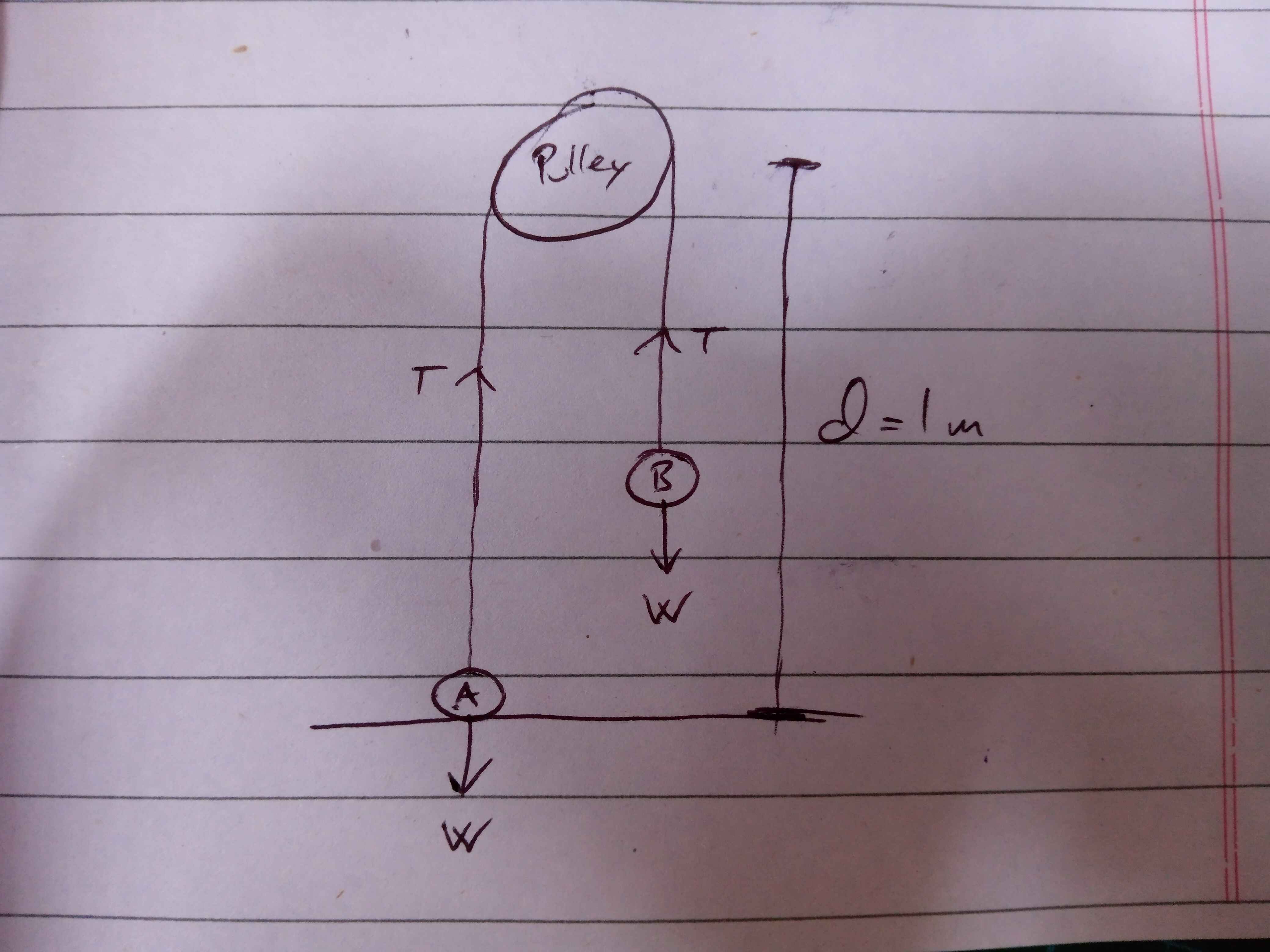

Two particles A and B have masses kg and kg respectively. The particles are attached to the ends of a light inextensible string which passes over a small fixed smooth pulley which is m above the horizontal ground. Initially particle A is held at rest on the ground vertically below the pulley, with the string taut. Particle B hangs vertically below the pulley at a height of m above the ground. Particle A is released.

Find the speed of A at the instant B reaches the ground.

(Question from 9709, October/November Paper 43, 2017.)

I'm not going to solve the entire question but I'll go as far as forming equations for the acceleration of A and B.

This is the situation:

We know that for both A and B, their acceleration is of the same magnitude, but opposite in direction. The tension in the string (unknown) is the same for both. Typically, in such situations, where both and are unknown, you'd create two equations (in order to resolve the forces) and solve them simultaneously.

Let denote the resultant force, denote the tension in the string, denote the weight of either A or B, and denote the masses of A or B.

These are the two equations you'd generally see. Most explanations I've seen tend to either neglect or barely explain why the second equation is that way. Why, now, are we subtracting weight from tension instead of the other way round? Sure, these two equations are convenient to work with, but why?

A nice way too look at this: we know that the magnitude of the acceleration is the same for both A and B. In other words, is the same for both. To illustrate this, let's set up an equation in terms of :

We'll do the same for B:

We now have four equations in :

- or

- or

All of these will yeild the same magnitude of acceleration. You can pick any two of these and solve for whatever you need.

This article was written on 2024-09-03. If you have any thoughts, feel free to send me an email with them. Have a nice day!